Dancing with Toots Benedicta

Toots Benedicta was my paternal grandmother, born in what was then Ceylon, now Sri Lanka, resplendent island, in the early 1900s, emigrating to Australia in the late 1940s. Her story is a complex one, and our relationship was a distant one. I remember meeting her only a handful times before she died. I wish that we could have danced together, like I did as a child with my maternal grandmother, oh lady of the soft-shoe-shuffle. But familial dynamics structured by race and class living under the spectre of the White Australia Policy, seemingly made this an impossibility. I’m sure she would have been a great dancer.

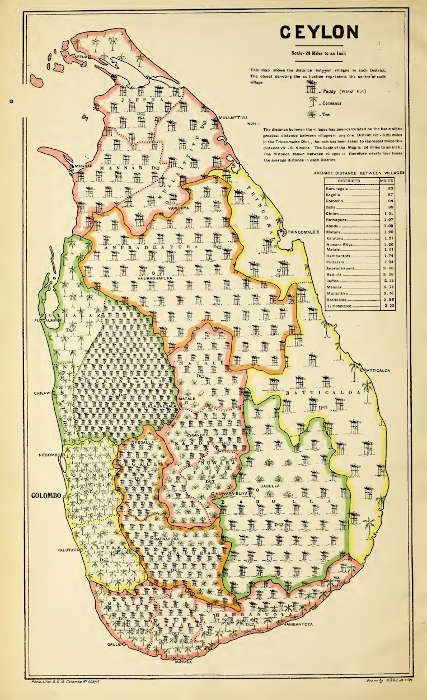

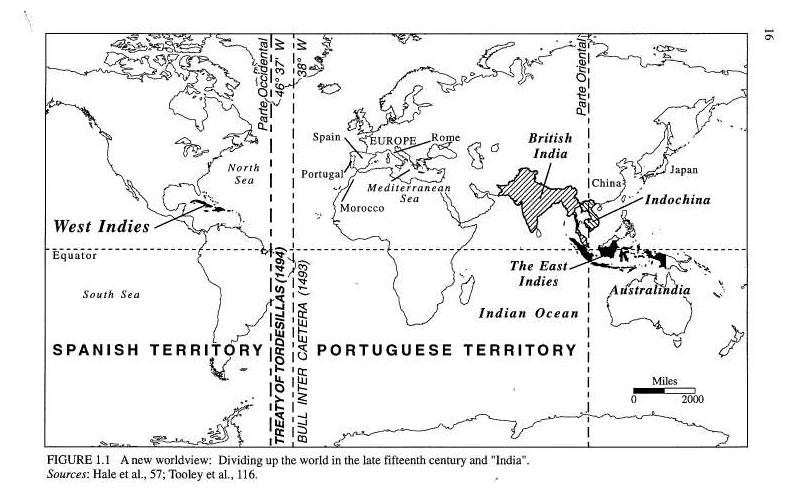

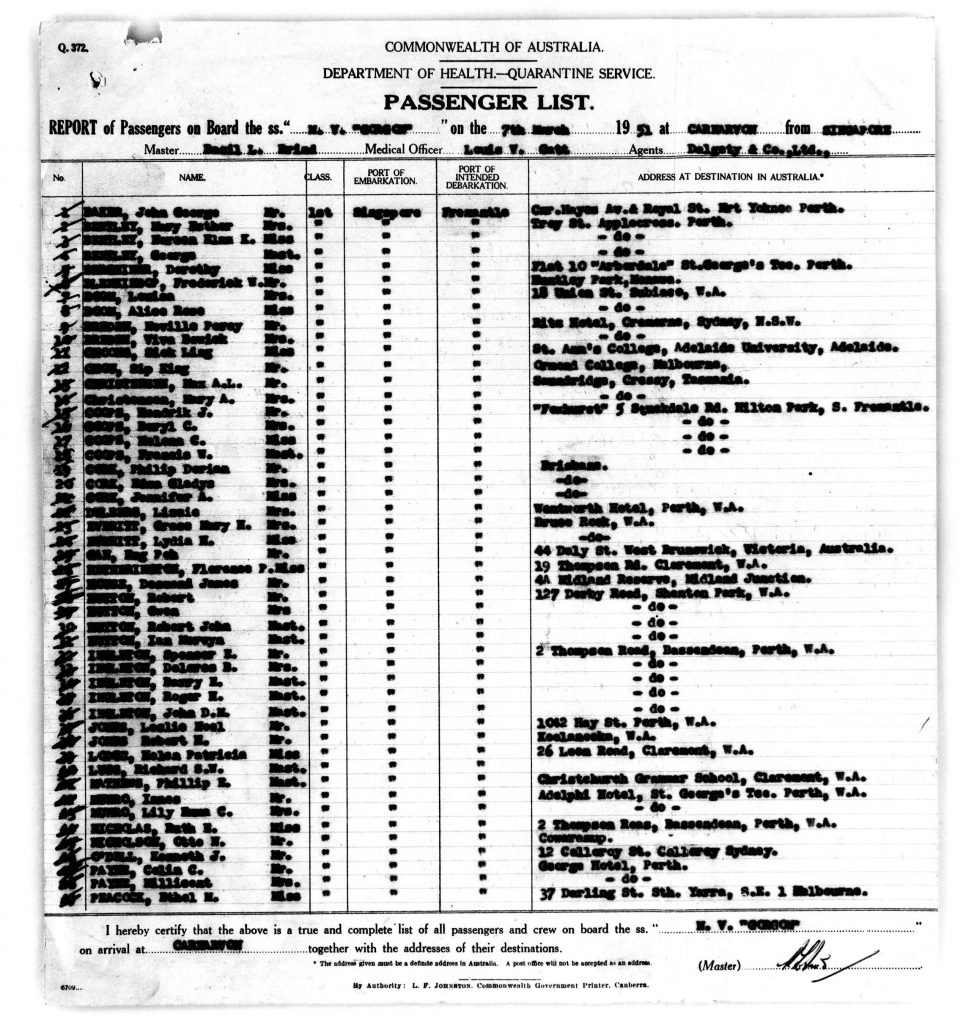

These last weeks have been full, of books, of sounds, of tracing the lost and the impossible. The histories of Sri Lanka, especially its colonisation by the Portuguese, Dutch and British. Searching for why my family left, how they were able to arrive in a country with an immigration policy of whites only, seeking to better understand who my ancestors might be, who they were. What was their role in the history of Sri Lanka? How were their lives shaped by the waves of colonisation? Why is everything so secretive? Were they running from something? Why don’t they fit any known narrative? What have I of them now? What have I always had of them? The fleeing, nomadic, running, slipping through regimes of documentation, never fitting, always mixed, fluid. Never this nor that. And on we go, dancing through the stratosphere of our intertwined-intergenerational-diasporan histories.

This page represents the beginning of something that I hope will grow, a new body of work, and a new, or at least some more developed, expanded, thoughtful and experimental ways of working in sound. Dancing with Toots Benedicta is what I want to do. This project, and this page, is a space for me to work out how to do this (checking privilege and thanking Arts Council England). Things will come and go, some will stay, ideas flash up and then move on. Some sounds, ideas, text, images will emerge, work in progress. I’ve been composing mostly using Supercollider, experimenting and learning and re-finding my creative-self.

How to write about a history that is at once so overdetermined yet simultaneously erased?

I begin looking back, the romanticism of the raga. The transcendental sounds of this ancient music, Joe Harriot, Alice Coltraine, Annapurna Devi. Its not a music I grew up with, but is one that I have always been drawn to, especially as facets of it emerged in the avant-garde experimental musics of the post-war period and of course in early techno and trance, ‘Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat’. Alap means introduction. I start to explore the form, the timing, scales, structure. It is like dipping my toe into a vast vast sea. I am overwhelmed.

On the EP, ‘Dancing With Toots Benedicta’, ‘Alap’ is an introductory improvisation of a repeated musical phrase. It consists of the first five notes of the South Indian Carnatic Raga Latangi, which in itself is the introductory section, called ālāp or alaap, of the raga in its entirety. I repeat these notes, as entry points to a world of complex patterns and relations, again and again in an effort to create a body memory, a muscle memory, where once there was none. I want to embody these patterns, to put them on, to wear them, to internalise them as a way of ‘organising the muddled, barely remembered fragments of a lost past to find, to create an emotional place within it’1. It is a beginning.

I undertake historical research of the island of Sri Lanka. From ancient history to the latest headlines, there is of course too much to take in. I will always be an outsider strangely umbilically attached to the land I have never been to. My racial heritage was minimised when I was a child growing up in Australia, 1/2, 1/4, 1/16, like musical notes, almost.

My father, born in Ceylon in 1948, distanced himself from his family of origin, my Sri Lankan grandparents, uncles, cousins. He also distanced himself from my family of origin through divorce, leaving me, the only obviously brown child, to be raised by a white family with antiquated ideas about race and blackness. In tandem I start trying to trace my own ancestral heritage in Sri Lanka and to learn more about the colonial history of the island. I have a colonial name. This, the obvious fact of my paternal family’s brownness, their Catholicism and the fact that my father was born in Kandy are all I have to go on. It is enough and no where near enough at the same time, enough to get me lost in searching for names.

The history of colonialism is confronting on many personal levels. Nira Wickramasinghe writes of the histories of colonisation in ‘A Modern History of Sri Lanka’. I search censuses of the early 1900’s, I find racism, words for being mixed, racist words. I find histories of inter-mixture, creole, poverty, disenfranchisement. The violence of the British. I focus on the period of independence, searching for some understanding for why my family left. The Colebrook-Cameron reforms and the Ceylon Citizenship Bill of 1948 that disenfranchised so many, the effects of which seem largely to have defined the future of the island. The ‘modernising’ project of the British. The introduction of mechanisation leads me again through Wickramasinghe, to the phonograph as a ‘Metallic Modern’ introduced to Sri Lanka by what looks to be a distant relative of mine.

I feel ashamed, but I knew very little about Sri Lanka at the start of this project, other than that’s where my father and his family are from, that I am half Sri Lankan. In Australia as a result of the country’s demand for assimilation to the supremacy of whiteness and the resulting internalised racism of my father in particular, there was never any pride or celebration of any kind of Sri Lankan heritage in my upbringing. We were never part of any Sri Lankan community in Australia, neither Sinhalese, Tamil nor Burgher. As a result, being Sri Lankan has always been a part of me that I’ve known and carried in the world, but not something that I’ve ever explored in any great depth. My job in my family of origin was to also assimilate into whiteness, which of course caused a few problems here and there, but in the 1970’s in Australia, there just didn’t seem to be any language to address feelings of otherness, so I internalised it and buried these feelings, to be returned to at a later date.

But where are you really from?

The phonograph presents as an entry point into this history and has always been a beloved instrument for me. As a youngster I commandeered the neglected record player in my family home, ‘borrowing’ records wherever I could find them. Later taking up deejaying, mixing, conjuring sonic worlds through the combination of frequencies, melodies, beats, and tones proved to be a life-affirming, world-making practice.

Finding gramophone recordings from Sri Lanka in the 1930’s-40’s felt like a gift. I am most interested in the traces of the human hand in these recordings, the mistakes, spectral artefacts, traces of the people who made them, listened to them, and the sonic identities that sing, play and stutter through them. But I am also aware that these are Sinhalese recordings. I am part Sinhalese. But again, this history is one that has been denied me, whilst simultaneously having its own ongoing history of supremacist violence. I am interested in the noise, the traces, the flaws and failures,

“…where history appears as a groove that indexes both the indentations found on the surface of the phonograph records and those somewhat more elusive grooves in the vernacular sense“

(Alexander G. Weheliye, Phonographies, p. 73)

‘Dancing With Toots Benedicta’ closes with a meditation. ‘Channelling’ is a transgenerational séance, a way to commune with lost ancestors through lower Shruti frequencies derived from the classical Indian Just Intonation tuning system. It opens a pathway to tune into the unheard, searching for the differences and combinations that momentarily emerge and dissipate through the merging of frequencies. To me, these sonic psychoacoustic effects resemble my experiences of mixedness, of merging and emerging, of masking and code-switching, as a kind of double aurality. The difference and combination tones emerge, blend, dissipate and re-emerge, as do all the different parts of my identity. The long drone connects Sri Lanka and Australia through ancient histories, transporting me to a kind of home I never knew before.

Released February 14, 2022

Programming, composition and performance by Lee Ingleton

Mastered by Queer Ear Mastering

Supported using public funding by Arts Council England

1Dina Georgis, The Better Story: Queer Affects from the Middle East, (Albany: Suny Press, 2013), vii.

2Ann Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality and Lesbian Public Cultures, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003).

3 Nira Wickramasinghe, Metallic Modern: Everyday Machines in Colonial Sri Lanka, (New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2014), 2.

4 Mica Cardenas, “Trans of Color Poetics: Stitching Bodies, Concepts, and Algorithms”, The Scholar and Feminist Online, 13.3-14.1 (2016): https://sfonline.barnard.edu/traversing-technologies/micha-cardenas-trans-of-color-poetics-stitching-bodies-concepts-and-algorithms/

5 Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition, (Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 65.